The little mosque inside the alcazar of Jerez de la Frontera has been restored as much as possible to standards of contemporary European ecumenicism. It exists as an ideal of pure architectural forms: arches, dome, courtyards, fountains. The only hint of decoration arrives on the breeze, a strong fragrance of orange blossoms from nearby orchards. The name of Allah is nowhere to be seen in Arabic script; if there were tiles once, they have long ago been stripped and somebody had the good grace not to make inferior reproductions; no prayer rugs are spread on the floor only woven mats, sand or stone colored like the walls. The exception is the mihrab—the niche indicating the direction of Mecca. There's a tiny pedestal with nothing on it, so the niche is both empty and, in a sense, not.

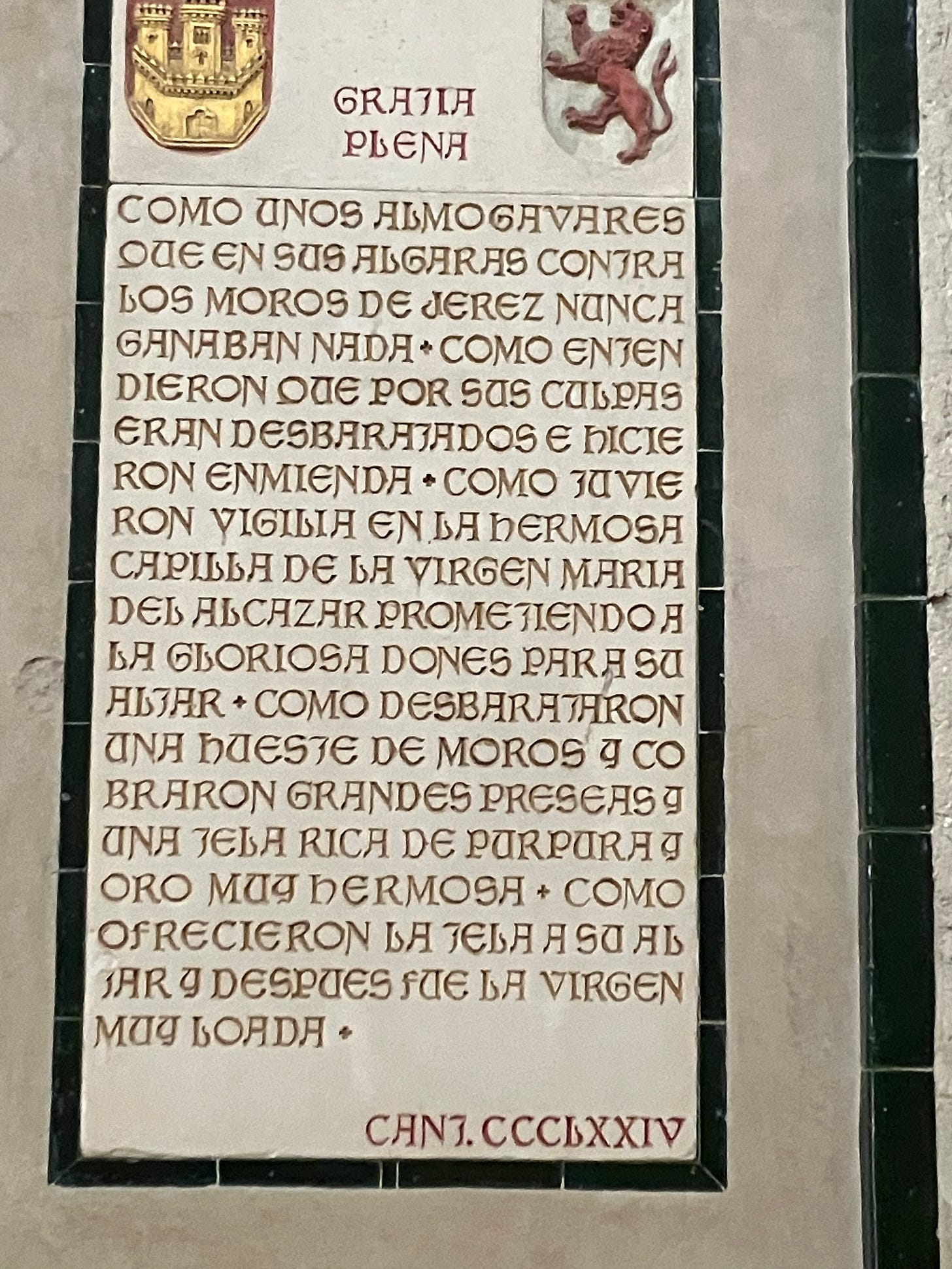

Additional incongruities: beneath the mihrab stands a large wooden chest engraved with the arms of the kings of Castile-Leon; it is additionally flanked by two large format posters containing texts from the "Cantigas de Santa Maria"—purportedly composed by King Alfonso X himself—to honor the Virgin Mary for her assistance with the conquest of Seville in 1254 and then Jerez in 1260 along with other later successful campaigns.1

The text to the right tells of some "almogavares" of Jerez, who, having gained nothing in their raids ("algaras") against "los moros," prayed in this very spot, in the lovely chapel of the virgin of the alcazar, and kept vigil all night before her image, after which they won much booty, including "una tela rica de purpura y oro muy hermosa." This "tela," a cloth of heaven (or really of Islamic-Andalusian design and manufacture) they spread upon the altar, but they did not tread softly upon it. Unspoken in Alfonso's song is that their spoils doubtless included men and women whom these informal and mainly mercenary soldiers sold into slavery or kept for their own domestic abuse.2

I am standing where these Christianized marauders once stood or kneeled, looking at the same spot where they fixed their attention, lifting my eyes up to the dome of the mosque and its feeling of heavenly expanse as they too might have lifted their eyes. There are moments when you can feel as if you are staring through a window down a long vista in time, in which history becomes, as the cliché has it, present—although this presence is never direct or precise.

What on earth, for instance, were these dudes thinking or feeling here in this place, only recently consecrated to their religion, which some of these merry bandits may have themselves only recently adopted? The very names by which they were known—almogavares or more often almoghavares—is a romanization of an Arabic word for raider, along with their deeds (algaras or algarabes—raids). They were praying to a virgin mother to help them carry off someone else's mother to make her a whore. The incongruities were a little overwhelming, or felt so to me, though perhaps not to them.

If I felt I were seeing history, I was nevertheless seeing history through history. We are in an epoch when we have ever more myths about our myths. The so-called "Reconquista" was a myth; there had been no unified Christian kingdom of Hispania when a mixed army of Arabs and Berbers crossed the straits of Gibraltar in the early 8th century with the aid of disgruntled local Visigothic chieftains (migrant invaders themselves from what's now the Balkans). Neither was there Europe. Whatever reactionary French pseudo-thinkers like Renaud Camus want to think about the Battle of Tours or the Song of Roland—composed 300 years after the events it commemorates—and whatever they spout about "Great Replacements," everyone was already a mixture of tribes, new and old, Celt, Frank, Latin, Hun, Viking, Lombard, Visigoth, Basque.

Like Christian Europe, The Islamic kingdoms of Al-Andalus had to be invented and reinvented. Much celebrated by elite Western universities in the early 2000s as a forerunner of the type of elite, cooperative, globalized pluralism for which they themselves were standard bearers,3 what truly was—for a time—one of the world's great multicultural civilizations also began as a conquest for land and loot. Al-Andalus had to be given meaning and form by those who created it, and some of those forms undercut the meanings.

For instance, both the Arabic word qasr and the Norman-English castle derive from the same Latin root for encampment (castrum). The alcazar of Jerez was conceived and built as a fortified camp in hostile territory by the initial Moorish conquistadores, then enlarged by the much later Almohad dynasty after they'd seized the town from a different group of Moorish overlords during one of the dizzying array of feudal wars that make up the political history of medieval Spain and the medieval world generally.

The useful wall texts hung around the site indulged in geeky description of the military aspects of fortifications: This little bricked up archway had been a hidden gate to surprise attackers and allow resupply; the hole above your head meant for boiling oil; there were arrow slits and underground well systems with their own defensive bastion. Everyone loves the word bastion! Here's the kind of stuff meant to fire the imagination of the kind of boy I was and part of me remains still. What is a fort without a siege?

I couldn't however avoid the thought that these texts themselves might contain remnants—largely unchanged—from the era of Falangist—i.e. explicitly Christian Fascist—Spain, that there was a political dimension to all this emphasis on the warlike intentions of what was otherwise, on this fine, orange-scented afternoon in late March, a place to drift about dreamily amid peaceful Romantic ruins, musing on the cultivation of different species of orange while trying to understand how the fruit migrated from China to Southern Spain.

The wall texts also pointed out the disconcerting fact that the fortifications were strongest on the side facing the old town of Jerez—the modern city has grown up around it and the alcazar now sits basically in the center of a downtown amid squares and apartment buildings with the famous sherry warehouses downslope to the river. (You can see the headquarters of old Tio Pepe, who pioneered fortification of a different sort, wine dosed with extra sugar to preserve it on long sea voyages to New Spain. ) If we believe the guides, the alcazar was not designed to protect the town from invaders, but to protect the invaders from the town.

In other words, I was being led to understand that I was standing inside a colonial structure from a period that most contemporary invocations of colonialism consider to be somehow pre-colonial. The Jerez alcazar became a center of Islamic civilization and ways of life, sure, but also for the propagation and spread of that civilization amid a restive population that was never wholly trusted. Not only did the castle hold the mosque, it grew to house harem apartments, gardens, an administrative center, even a hamam that its Christian conquerors—having no use or concept for regular bathing— converted into kilns for ceramics.

The contradictions of the Christian soldiers with Arabic names—who took their tactics and practices from generations of Berber raiders before them, only this time under the sign of the Virgin Mary— were starting to seem more comprehensible (They were building a new master's house with the old master's tools, except they didn't build the house, they only took it over.). The eventual inventors of European colonialism—at first— had to have considered themselves to certain degrees as colonized.

This thought made the flatness and the lack of self-consciousness of the description in Alfonso's canticles somehow more depressing. Did these soldiers have no sense of irony? Was irony, like ambivalence and self-detachment, truly a modern invention that only arrived in Spain around the time of Cervantes? Did these men truly lack all feeling for the spirituality of the mosque or for the divine feminine they worshipped there?

I share these thoughts with my traveling companion, herself a historian of empire. But she is not very impressed with my attempts to think my way into the mindset or lack of mindset of the almoghavares, ignorant warlike men from another ignorant and warlike time. The previous night we'd shared our impatience with the Left's sudden mania for historical comparisons and analogies between the present moment in the United States and the 20th century rise of European fascism. "Is it 1933 or 1935?" my companion asked rhetorically, "what month in 1935, what date?" All we can say for sure, we agreed, is that we're living in a period when certain classes of people, educated in a certain way, find it very important to locate themselves within a timeline based almost exclusively on 20th century events, a sort of typological thinking that has more in common with earlier religious epochs than supposedly rationalist modernity. Thinking with history thus becomes a way of thinking ahistorically, of making everything into a kind of passion play, an eternal recurrence. Maybe it's 1935 for you, but for someone else maybe it's 1395!

The same forms too get repurposed for new scenes, the way a mosque becomes a church, or the way a Moorish alcazar becomes a Spanish colonial mission. From the top of Jerez's octagonal tower, looking out over the Guadalquivir flatlands, one can thus see all the way to the "New World," and the castrums that Christian Castilian conquistadores would later build in Mexico and California and the border territory now known as Texas, one of which would become the origin of one of the greatest and stupidest myths of US Manifest Destiny now fueling an absurdist ideology of new American expansionism under, of course, the sign of a repetition: "Make America Great Again."

Why did I choose now to remember the Alamo? An American friend here in Lisbon had recently gone back to visit family in the Rio Grande Valley and had sent photos from a daytrip to San Antonio that included him posing ironically in front of the mission turned holy place of American expansionist martyrology. That image was part of my mental weather: and there is something about the interaction of mind and form that invites us to indulge comparisons: Hey, the conquest of Mexico, the beginnings of the Atlantic slave trade, and the European great power competition that resulted in a bunch of anglos taking land from a bunch of latinos in 1836 and again in 1846 really did originate in the near-abroad of the Iberian peninsula, amid the raiding and the slaving, and the porous ever-shifting borders of what the town's name still testifies to as a frontier!

But most likely I am remembering the Alamo alongside the almoghavares because my time in Jerez coincides with the publication of the briefly infamous national security group chat on Signal between Pete Hegseth, Michael Waltz, and J.D. Vance and others, thanks to their slapstick inclusion of Atlantic Magazine editor Jeffrey Goldberg. If I was wondering what was going through the minds of Alfonso X's warriors in their vigil at the mosque, their total unselfconsciousness, however excusable on medieval grounds, it's also because I was succeeding at screening out what could be going through the minds of our new American warriors—these self-proclaimed "men of faith" and Christian soldiers4—while they were dialing up the bombs on Yemen, and, as they were doing so, broadcasting contempt for allies and cruelty instead of the Christian virtues of love and compassion they claim to uphold.

The irony in this case is not that different from raiders praying to the Virgin inside the reconsecrated mosque. These men now spend their days inside structures designed to maintain and celebrate the opposite of the Christian sectarianism they now openly profess. The niche of American democracy has not yet been filled with an icon of any particular saint or holy figure.

Leaving the alcazar, my companion and I find Jerez’s Plaza das Armas full of men and women dressed in black knee breeches, white ruffled shirts, crisp white, red, or yellow stockings, shoes with large gleaming polished buckles, black capes and a variety of headgear. Some carry lutes, others guitars, others tambourines and recorders, some are there to sing. They are all members of so-called Tunas: originally 13th century bands of roaming university students who sang for their supper, the tradition has been carried on through the 21st century as cosplay competitions between literal minstrels. Usually they are students, somewhat like acapella groups at US colleges, but the Tunas we are seeing look middle-aged or older, pot-bellied, gray-haired, balding, still vigorous, strumming and serenading, applauding each other, tossing back cups of sherry.

These people do not yearn to dress in the borrowed livery of past ages and ideological conflicts between “Islam” and “The West” or the authority and stability of Catholic doctrine against the heresies of secular, modern emancipation. They literally wake up and put on the clothes of another time in order to sing songs, some as old as madrigals, others that sound like flamenco-tinged Rock n’ Roll. If, throughout history, we are always to beat on, boats against the currents, borne back ceaselessly, I know the boat I want to be on.

The Feckless Bellelettrist being—well—both feckless and a bellelettrist, all historical facts and authoritative-sounding pronouncements about Andalusia are thanks to Brian Catlos's remarkable synthetic and comprehensive history Kingdoms of Faith: A New History of Islamic Spain; Oxford University Press, 2018. I am not so feckless as to be unaware of the dangers of relying on a single source when writing about history, but I’m also happy Catlos has done the work of telling a good, clear story from a representative diversity of assembled sources.

For the general warring practices of both “moros y cristianos” in 13th century Iberia during the period leading up to the conquest of Jerez, and how the various borderlands between Moorish and Christian kingdoms were transformed into “a society organized for war,” see Catlos, ch 20 pp. 265-269 and chapter 23.

for an explicit though by no means exclusive example of this kind of thinking cf. Maria Rosa Menocal, “Culture in the time of tolerance: Al Andalus as model for our time,” lecture given at the closing dinner of the Middle East Legal Studies Seminar (MELSS), Istanbul, Turkey, May 9, 2000.

For Hegseth’s militaristic neo-Crusader views, see https://www.nytimes.com/2024/12/05/us/hegseth-church-crusades.html. For the protean Vance’s conversion to Catholicism and his interest in what no journalist has yet dared name as “Falangist” elements of contemporary Catholic teaching, see Paul Elie in The New Yorker, https://www.newyorker.com/news/daily-comment/j-d-vances-radical-religion

I really liked this a lot. Metahistory of the most interesting kind. Not feckless at all.